Studia Nova: Reinventing K-12 Education

Imagine an effective and inexpensive K-12 education, delivered in half a typical school day, that rejects failed teaching methods, ideological prejudices, and bureaucratic red tape.

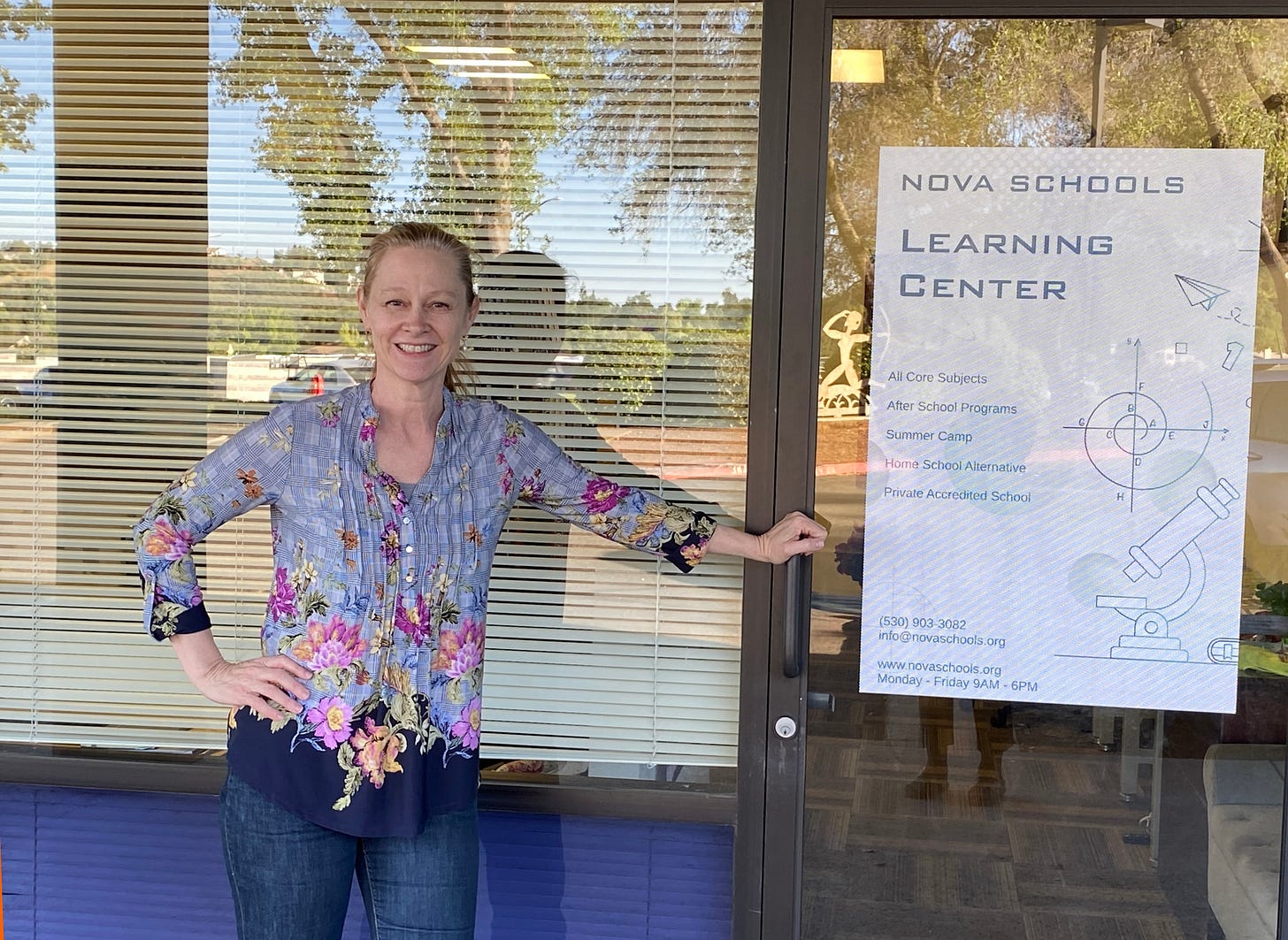

Proof-of-Concept Interview with Victoria Garmy

Victoria Garmy heads StudiaNova.org, a K-12 academy that is reinventing primary and secondary education. Garmy has introduced an innovative learning model that is decentralized, scalable, affordable, efficient, and readily implemented. This model puts the high-tech learning tools of today into what is essentially a one-room school house.

Garmy’s micro-school approach to K-12 education works remarkably well. In a few hours a day of intense focused learning, her students excel, assimilating more in less time. Her model does an end run around the corruption and fecklessness that infects so much of American K-12 education. In this interview, Garmy presents a convincing proof of concept for her educational model.

DISCLAIMER: As of May 12, 2024 when I, Bill Dembski, posted this interview, I have no financial stake in StudiaNova.org and am receiving no remuneration from that organization. That said, I’m sufficiently intrigued with Studia Nova that I could see investing in it at some point down the line.

Bill Dembski:

Thanks for agreeing to this interview. You recently gave me a virtual tour of your school and explained to me the key aspects of your approach to K-12 education. I was so intrigued that I would like to get the word out more widely. My hope is that this interview will help you gain valuable feedback and allies as well as inspire others to adopt your model, or variations of it, in ever greater numbers. But before we get into the details of your model, tell us something about yourself. Where and when did you grow up? What was your family life like? What role did religion play in your early life? What things interested you most in your early formative years?

Victoria Garmy:

I grew up in a very rural area of California. My parents left the Los Angeles area in the mid 70s and moved out onto the land. They were city kids playing country. But I can’t imagine a more idyllic childhood. Plenty of room to roam, plenty of cold well water, plenty of home-cooked dinners. We loved the animals, building forts, gathering eggs, weeding the garden, canning vegetables, bringing in the firewood. We loved our normal, regular life. Mom and Dad worked in town and we were just free ranging it until they came home and made dinner. It was heaven on earth.

Religion was just a normal part life. Everyone had some kind religion. There were Mormons and Catholics, but mostly Protestants. We didn’t know of any atheists and there certainly weren't any satanist clubs in school. Immediately after high school, I went to a local community college, about two hours away. At the end of the term, the physics professor handed each one of us a little Bible as we walked out of class that day. That little Bible felt just normal at the time. So I guess I would describe my early experiences with religion as ordinary, a natural part of the social milieu I grew up in. Where and when I grew up, “controversial” ideas like Intelligent Design would have just been assumed true.

Bill Dembski:

Tell us about your elementary and middle school years. What did you enjoy most during those years? What were your extracurriculars? How big a role did athletics play during your high school years? Tell us about any teachers from that time that particularly inspired you.

Victoria Garmy:

We all attended a one-room school house run, in fact, by the local preacher’s wife, Marilyn Seward. I still remember the first and last names of all my teachers and all the kids I played with day after day from kindergarten through eighth grade. It was the last of its kind. I think it held together against county budget cuts by the shear will of Mrs. Seward. Our math books were old because she would not buy “new math” text books. We worked our problems under her watchful supervision.

There was no homework. Mrs. Seward knew most kids went home to chores and it would not be done anyway. Of course, I did not know I was getting such a great education at the time, but only later when I went to high school, and on to college, did I realize how much I relied on that incredible foundation I acquired in the early grades.

In the time and place I grew up, athletics had not risen to the importance it has today. Athletics was just about the fun. We would play volleyball after school, then travel to other schools to play with them. We always lost, but no one really cared that much. I think we just liked all riding on the bus somewhere together. I learned to play oboe, but admittedly rather poorly. We had a neighbor that was a music teacher, and we all went to his house once a week. I think we even paid him in bartered goods and chores rather than cash.

Bill Dembski:

Tell us about your high school and college experience. What led you to go to the college you attended? Did your high school prepare you well for your time in college? How could your preparation have been better? What was your major?

Victoria Garmy:

When I left Mrs. Seward’s one-room school house for high school in the nearby town, I mainly just goofed off. My levels were so far above everyone else who came from different grade schools that it did not take me long to realize I could wing it. In general, high school was academically of minimal value; I would say it was purely about making new friends. If I had continued in the framework of my earlier education, my high school years would have been a much better use of time.

After high school, I started at a local community college, with the intent to transfer to a four-year university and major in engineering. Community college was a fantastic time to build up the maturity I needed to complete an engineering degree. I earned a bachelor’s from the University of California at Davis with a double major in mechanical and aeronautical engineering. I did not work long in aeronautical engineering. Instead, I moved into technology and software since there was so much going in those areas at the time. I’d do it all over again in a heart beat.

Bill Dembski:

How did what you learned as a college/university student help you once you entered the real world and had to make a living? Describe your employment history to the point where you began seriously to rethink K-12 education. What’s been your main day job?

Victoria Garmy:

My own educational experience was fantastic, but it really started bothering me that many young people were not getting anything close to what I had. I felt an overwhelming need to do something. I had toyed with getting my teaching credential. But at the same time, my mother had just retired, and she was a certificated public school teacher. She was interested in teaching and I was interested in tinkering with education technology. Together, we basically invented our current approach. The engineer in me wanted to re-engineer education and give today’s students something of what I had received.

Many of the companies I have worked for over the years provide software solutions to various government agencies. More than anything, my career taught me that government agencies have a tough time making purchasing decisions. This is why schools are not really leveraging technology to get better outcomes. I knew I could design the technology to the benefit of the student.

Bill Dembski:

Your worldview shifted just before you started rethinking education. Describe some of the key influences that reshaped your worldview. How exactly did your worldview change? As your worldview changed, why did you feel the need to focus on education?

Victoria Garmy:

As a STEM (science-technology-engineering-math) major and working STEM fields, I viewed the Bible as way down the list of important things to learn about. After all, we are engineers. We are rational. And reason and faith are polar opposites. For most of my life, I might have conceded a fluffy theistic evolution. Keep in mind, I never had a biology class in college. It wasn’t required for mechanicals.

When I was thinking about getting my teaching certification, I found I needed a life science credit. So I enrolled in biology at the local community college. I was thunderstruck at the complexity of the cell and its mechanical inner-workings. Eventually, I wandered into a few videos by Stephen Meyer, and I bought one of his books (Signature in the Cell).

I read that book over and over and over before I was able to let go of years of Darwinian evolution indoctrination. Once I got out of my head the crazy idea that this wondrous universe is all some kind of happy accident, the question of faith as opposite to reason became irrelevant to me. I didn’t need that kind of faith because I had good reasons that there is a creator. For me, the word faith no longer means blind trust. It means loyalty to our creator in heaven. Faith means fulfilling my purpose.

My testimony is not for everyone. A very close friend of mine has, since she was a small child, been able constantly to feel her faith. She feels the presence of Jesus in her heart and even cries simply when his closeness overcomes her. My testimony is for those who are not so wired. Some of us need that hard logic that Intelligent Design’s principal players offer.

Bill Dembski:

Before getting into the details of Studia Nova, let’s turn to your broader vision for American K-12 education:

What should be the main goals of K-12 education?

Which aspects of the current state of K-12 concern you the most?

What values do you believe should be instilled in all students, regardless of their families’ backgrounds or beliefs?

How can schools best prepare students for the challenges and opportunities of tomorrow?

The system is calcified and unable to improve, and we are losing our county because of it.

Victoria Garmy:

K-12 is way off course. So called experts are continuously experimenting on students with new ways of teaching that never help. There are no community controls on what is taught. The school boards do not have any appreciable impact on what happens in the classroom. Communities are no longer being heard. They are being ignored. So it is clear the educational system is not serving families. It serves some other purpose. The system is calcified and unable to improve, and we are losing our county because of it.

Let’s say that K-12 should be singularly focused on academic outcomes. The challenge is that we cannot teach any work of literature without teaching a world view. There is really nothing that’s completely unbiased. I also cannot teach science without teaching a world view since there is so much scientism in our world today.

I have to establish a world view in order to teach basic logic and evidentiary principals. In history, the choice of which information to present establishes a world view. Every academic program has to choose a world view. There is no way around it. So the goal of K-12 is to raise academic outcomes from the perspective of a world view that creates happy, successful adults who are strengthened by knowledge and remain united with their families.

We have the commandment to honor our parents. An educational system must not seek to pull students away from the world view of their family, as this would entice the student to disrespect their parents. That is why I am so excited to integrate ID (Intelligent Design) into the curriculum.

ID is a logical framework that establishes a world view that belongs to all religions and all people. With the ID framework we can set students down the path towards a strong and persistent faith because they love this amazing world created for us and they know they must be created for an important purpose.

Bill Dembski:

The previous questions have set the stage for what is the focus of this interview, namely, your founding of and work with Studia Nova, a new and effective model for delivering K-12 education. Give us the background that led up to you starting this organization. Who were your conversation partners in setting it up? Did you set it up as a non-profit or as a for-profit, and why? Take us right up to the point of opening your doors to students.

Victoria Garmy:

Both my sister, who’s an MIT grad, and I “afterschooled” our kids. We knew what students needed to learn to be successful in STEM fields, both of us having completed engineering degrees. Our own kids had the advantage of our knowledge, but many, many kids did not. I launched the school when I was convinced we could do a better job of it. I identified the technology stack and road-map, went down the wrong pathway a few times, then outlined and executed the development plan. My mother was the main teacher and worked directly with the students, and here we are today.

We founded the technology company as an LLC, and we personally funded the entire investment. The LLC structure holds the technology and curriculum platform. However, it is difficult to set up a school and not lose money, so we recently partnered with a non-profit (Nova Schools) whose purpose is to raise money to help students with tuition and to help set up additional schools. The non-profit also advances our faith and world view perspective. We are in the process of moving the non-profit forward and working to engage our community to increase its effectiveness.

It was a very important to us that we produce a cost effective and high quality form of education. We did not want to rely on endless donations, or be beholden to grant funding. The education system we wanted to create had to be financially independent at a price that parents could afford. We rented our first office space, put in some desks, retrofitted some cast-off computers with Linux and opened for business. Our first student’s came from my son’s boy scout troop. After that, they started trickling in from word of mouth.

Bill Dembski:

You gave me a Zoom tour of your facility. The facility is quite modest, which I mean as a compliment—the education you offer is cost effective and doesn’t waste the time of teachers or students. Talk us through your facility. Where is it? How much floor space is there? How is the space organized? Where do students spend their time? What are rent and utilities? What is insurance? What did it cost to equip your school (computers, furniture, etc.)? Where did you get the funding?

Victoria Garmy:

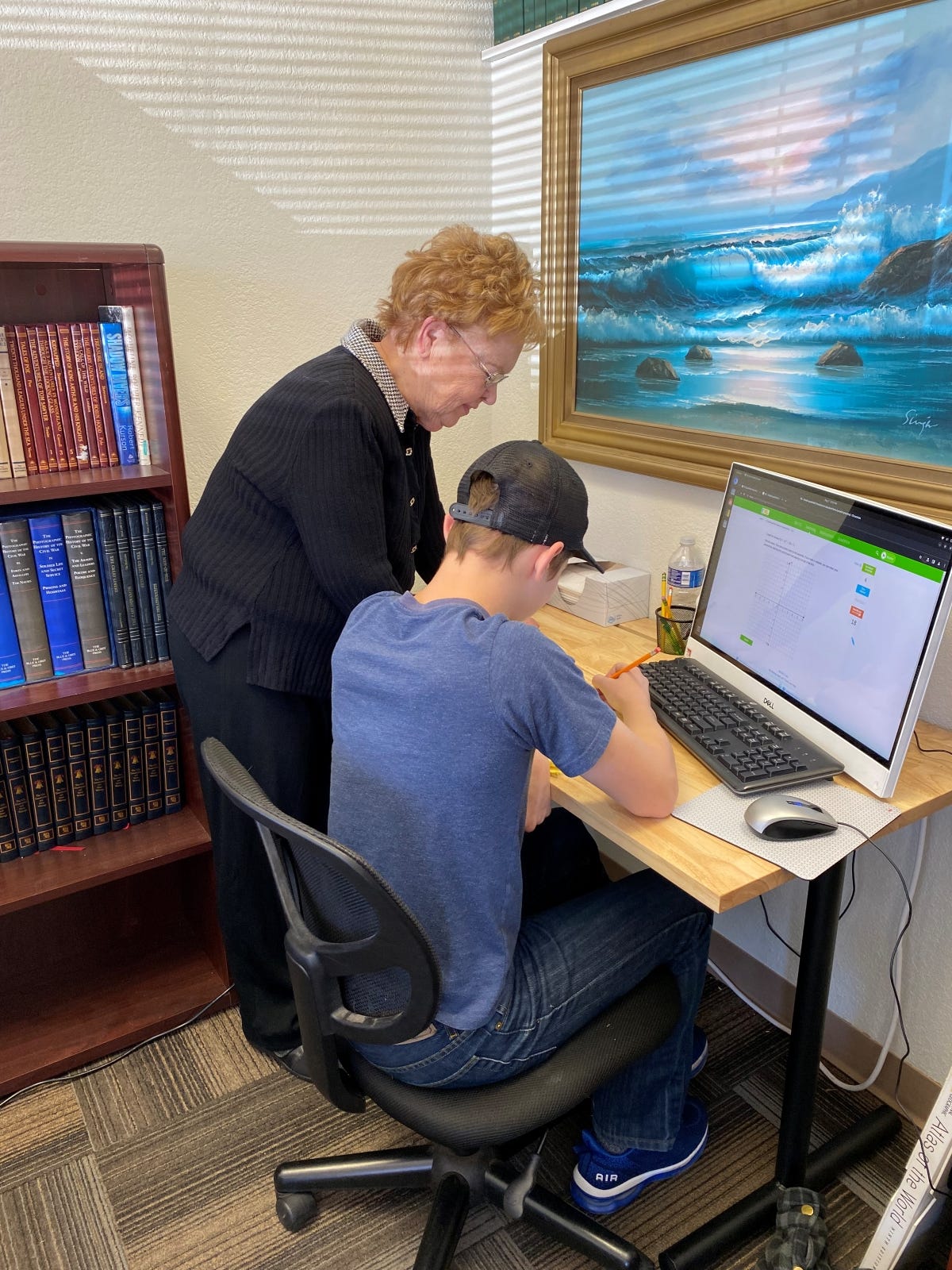

When talking about a facility, many people are get confused because we are virtual school. The facility embodies a very simple concept: just as when we go into the office and work on computers, students go to their office and work on computers. In a factory approach, the bell rings and everyone gets to work. Our facility takes a “white collar” approach: students are more like employees who show up and log into their workstations. The teacher helps the students when they get stuck, and then grades any assignments that are not auto-graded by the system.

It’s California, so utilities are the worst bill we have to pay. Right now, we are lucky that the commercial owner is helping us out with rent abeyance, which can be important to starting up a location. Insurance is not as bad as most people imagine, about $1,200 per year. The location operates more like a tutoring center than a typical school. Desks and computers are not as expensive as people might imagine. Students only need access to a browser. We use corporate cast-off computers with Linux and never have any operational issues.

To start up a location, you would want about 20 student desks, or workstations, which would be about $10,000 and they would last about 5 years easy enough. Since students are at their desks for only a half day, the location can serve up to 40 students. We don’t need other facilities like lunch rooms, break rooms, gyms or anything else because students are not onsite long enough to really need any of that. Operating a school is a lot easier if you are not doing food or PE, so we don’t do food or PE. On occasion, one of our parents will plan a class art project, and we clear a space for an art day. The students love that.

We found that a mixed grade level is optimum. A few little ones in a mix of middle and older students is the most manageable configuration. We are targeting the tuition to be $3,600 per student per year, so that a single location would pull in $144,000 annually, without counting in any additional summer term revenue. Our system is meant to enable small one-room schools to be run as a reasonably profitable small business without reliance on endless donations.

Bill Dembski:

Who are your students? From what applicant pool are you drawing? Much time is wasted in public schools with disciplinary problems. What is your tolerance for students with disciplinary problems? Do students wear uniforms?

Victoria Garmy:

We do not have disciplinary problems. Behavior problems are invariably the result of boredom. Our students are engaged in coursework that is appropriate to their level, and they get the help they need if they are frustrated. It helps that they can be done in 3 hours. Most kids know they can keep it together for 3 hours.

On the odd occasion when a student was out of line, I would just offer them to go back to public school at 6 hours a day plus 2 hours homework, for an 8 hour school day. That tends to solve the problem. Also, when the school is a family choice, teachers do not have to deal with students who just don’t want to be there at all.

We want to encourage other people to start their own classrooms, and to leverage what we have built so far. So our school model is to let the person running the location make the policy decisions about uniforms and the like. Thus, if a local teacher wants to do uniforms, then that location could do uniforms.

Our students are typically the more challenging ones—the tough nuts. Their parents find us because they are looking for alternatives. Public school was not working for them and most had already tried online charter schools with poor results. I am deeply appreciative of our toughest nuts because they taught us everything we know. If we can teach them, the advanced kids are a piece of cake.

Bill Dembski:

What is the cost of your education to students and parents? To parents, how much are they looking at out of pocket? Are vouchers available to them. To students, how much time are they spending within your walls? You mentioned in our virtual tour that you have two three-hour sessions per day, in the morning and in the afternoon. You also mentioned that students could even do both the morning and afternoon sessions. How many do that, and do these students learn twice as much?

Victoria Garmy:

We do not accept vouchers. Parents pay out of pocket the full cost—$400 per month, or $3,600 for the school year. In California, vouchers are not available for private schools. They are only for students attending public charter schools. We want to stay focused on private since private gives us the widest latitude to create the best system. Many parents don’t even feel the tuition as they are used to paying more than $10,000 a year for private school. Others do have a hard time paying.

Our primary challenge is getting past what parents think a school should look like. When parents visit a school, they want to see the playground and the art pictures on the wall. When they visit my website, they want to see pictures of happy kids smiling while doing science projects in goggles. They are moved by nostalgia arising from their own school experience.

Our team is all about the academics, so we don’t invest in the nostalgia, though doing so would probably help us. I’d say this is our biggest challenge to adoption. However, once a student enrolls, our families are very sticky. Their life becomes much less complicated, with no arguments over homework and just knowing that their students are learning and getting ahead.

We have had students do longer days, such as a double session. In that case, productivity tends to fall off. Students will take their time when they know they have to stay longer. They are certainly less focused. All and all, students who work longer learn more, but the inefficiencies increase after the three hour mark.

Bill Dembski:

In K-12 education, students get the summer off. This is an artifact of former times when kids were expected to help out on the farm during summers. But that need is now passé. Three months off means students will unlearn and regress. How many days of instruction do you offer during the year, and how does that compare to ordinary public schools? Do you have any plans to increase the number of days of instruction?

Victoria Garmy:

We operate on a conventional school year, which is two terms from beginning September to end of May. Students only get “bank holidays” off during the term. There isn’t enough time for a long spring break or Christmas holiday. My parents love that part of our schedule. Our schedule allows us a long summer term, three months. The longer summer term allows us to offer a meaningful summer semester, allowing students to catch up on credits missed. Only about a quarter of my parents will choose summer school. Summer term costs extra, so this is a factor influencing parents’ decisions.

Personally, I see no need for students to take summers off. Parents are just paying extra money signing up kids for various camps any way. But summer is still part of the nostalgia of schooling. I’m still nostalgic about my summers, playing in the creek, the hot weather, sleeping in, the concept of endless vacation. But what we have now is really just video game binge months and a few camps that are really just baby sitting centers. I do hope more parents start to embrace year-round schooling. Our model easily accommodates a summer term.

Bill Dembski:

The role of large language models, such as ChatGPT, in helping students cheat on their assignments is a problem now throughout the academy. Besides cheating, students will cut corners wherever possible, making things as easy as possible on themselves. How does your approach counteract this temptation to cheat and cut corners?

When you teach to mastery, you take anxiety off the table.

Victoria Garmy:

I love technology, and technology solves many problems. There is no technology that can stop the creativity of students to figure out how to cut corners. There is only one solution: Watch them. The education system we advocate puts students under supervision. This is the most important part of getting students to make the right choices and learn.

We also reduce the stakes. Students take short cuts when they are stressed and worried about performance outcomes. We let students go at their own pace, take their time to learn what they need to learn. When you teach to mastery, you take anxiety off the table.

Bill Dembski:

What does a typical day at your school looks like for a typical student. How are they learning? How much are they learning in interaction with a live teacher? How much with other students? How do they move from subject to subject? How are they kept accountable for learning what they are supposed to be learning? How much of the time are they fully engaged? How much of the time are they spacing out? How do you keep them fully engaged? What do your assessments look like?

Victoria Garmy:

Students learn from doing, from reading, writing, and solving math problems. Most students do not learn very well from just listening to a lecture. When we listen to music, we learn something, but we will never learn to play an instrument by just listening. For that, we have to pick up the instrument and play.

In our model of education, students work under supervision, so there is a person there to help at all times. When students get help, it’s one on one. We also encourage students to help each other. This is teaching them positive social interactions, not negative ones. Some students do not want any help at all. It may surprise you to know that I have many students who flat out refuse help. They prefer to hammer it out by themselves. Others want help the minute anything get slightly challenging.

Students always “space out” when adults are talking to them. They space out in lectures and they also space out when you work with them one on one, just trying to help them with problems. It’s as though they have an instinct, when an adult speaks, that their brain must freeze. However, when they are working on their courses, they don’t space out. If students are distracted in class, it is because they are chit chatting with each-other, which is not altogether bad. A simple re-direction is sufficient to get them back on track.

Students have multiple courses assigned to them. We instruct students to do one hour on English, then the next hour on math, then the rest. But they never follow these guidelines. They always try to stick to their favorite subject. We have one 7th grader who only does math all day long. We really have to pester him to do any English. After we met with his parents, we agreed to let this preference run its course, as his reading levels are already above average. We reduced the scope of the reading program and allowed him to advance in math. The flexibility of the student information system and the course delivery platform, as well as accurate assessment levels are essential to being able to structure customized learning programs meeting the unique needs of students and their families.

Generally, courses have to be completed by the end of the term. The course delivery platform sends their scores to the student information system. Sometimes, if students are struggling to complete a course, we can let them complete it over the summer without impacting their credits, or we can split the credits over two terms. If students are really falling behind, we will restructure their program and provide them goals they can meet. We can also add a little extra time at the end of the day for them to catch up. We haven’t had any serious issues with students not completing their work.

Bill Dembski:

What do you do to ensure that the “three Rs” — reading, writing, and arithmetic — are not just learned but mastered? I talk to elementary school teachers who are discouraged that students learn multiple ways of doing arithmetic, but now no longer memorize their times tables and are incapable of performing basic arithmetic. It seems that phonics is still not the norm for teaching reading in public schools. And writing cursive, so helpful for mental development, after being removed from the curriculum is now starting to make a comeback, but is still not required in half the states. What say you about these crucial pillars of primary education, and how are you addressing them?

Victoria Garmy:

Math facts, algorithms, handwriting and phonics are the keys to college success. That is my personal experience and my experience in teaching others. It’s the only part of education we absolutely have to get right. The great thing about computers is that it really takes the pain out of memorizing math facts. There are plenty of games and activities that students can keep doing to learn the facts.

We further do not allow calculators of any kind until they start algebra 1. The algorithms, borrow and carry, long multiplication and long division are essential to drilling the accuracy required for higher level math. The algorithms are easy to teach and can be practiced over and over.

We take handwriting seriously with our own handwriting program — workbooks that accompany the online courses. If students cannot print legibly, they will not be able to read their own work on math problems. Phonics is essential to creating strong readers. Our early reading program is like phonics on steroids. Everything else seems to follow from these four essential areas of knowledge.

Almost a hundred percent of the time, students who are behind in math don’t know their basic math facts; and students who are behind in reading don’t know how to sound out words.

Bill Dembski:

What are the main resources you are using at StudiaNova.org? How much in the way of curriculum materials, books, and online resources are you, as it were, taking off the shelf? What in such cases have you found to be most beneficial to your students? How much of what you are giving your students is curriculum that you’ve developed? Describe any such curriculum and its effectiveness? Summarize your K-12 curriculum. Where does religious instruction fit in?

Victoria Garmy:

There is no shortage of curriculum out there. We have developed courses for K-12 in all subject areas mainly using free and open source material. However, for the 4th to 8th grade math program, we do purchase a subscription service so that we have enough math problems, graded automatically, to drive mastery. But mostly we build our courses using free and open materials.

For the early reading program, we use a phonics program called SoundBlends. SoundBlends teaches reading based on phonics. We also use the same program for remedial reading students.

Our first objective is to get all students to grade level within a term or an academic year. We readily meet this objective no matter how far behind students are.

I have written portions of the science program myself, mainly because I could not find material I thought was actually serious about science for about the 4th to 6th grade levels. In general, we have plenty of material to use to create our courses—we don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

For religious instruction, we are teaching the Bible stories appropriate to grade levels. We inform parents that we are teaching the Bible stories, and we also inform parents that learning the Bible stories is critical to understanding classical literature, since so much of it draws on biblical concepts.

We have recently launched an apologetics program for high school students, which is intended as a way to strengthen the college-bound to withstand challenges to their faith. As a college student, I felt the constant pressure to side with either the scientists or the faith community. We are teaching students this is a false dilemma.

Bill Dembski:

Talk to us about learning outcomes. What milestones do you expect your students to have completed by the end of 5th grade, 8th grade, and 12th grade? How much does your approach allow students to proceed at their own pace? What decides a student’s pace? How can students be encouraged to accelerate their pace? Given disparities in abilities and interest, and the ability to deliver education adapted to individual students, it seems crazy to keep students at a given age all plodding through material at the rate of the slowest learners? How do you redress that perennial problem?

Victoria Garmy:

When we started, we really wanted to encourage more students to enter the engineering fields. However, we had to pivot our focus when most students who came to us were incredibly far behind grade level in both reading and math. I didn’t realize how bad it was, and you can’t really get to a strong science and math foundation if students are three to four years behind grade level in reading.

We use a simple diagnostic to assess where students are relative to their grade level, mainly on a national scale. Our first objective is to get all students to grade level within a term or an academic year. We readily meet this objective no matter how far behind students are. We developed our processes of assessment, appropriate course assignment, then reassessment to address learning gaps. It was just classic feedback control. Academia is so open loop, and that is just so wrong to an engineering-type person like me.

In K-8, we have a lot of flexibility regarding the pace at which students want to proceed. It is not possible to teach to mastery if there is a hard schedule to complete the course. Students taking longer will just fall behind and get frustrated, and that is not the point of mastery. A flexible pace does make for some tough problems in record keeping, so most of our technology development was in the student information system—the record keeping part of running a school.

We have seen that if students come to us by the 6th grade and are reasonably on track, we can get them through algebra 1 before starting high school. This is really important to the college-bound because it allows students to take at least one year of calculus before starting college. For other students, getting algebra out of the way means they can usually graduate in 3 years instead of the usual 4.

High school is less flexible. In order to award the credits that students need for college entrance, students do have to meet basic pace requirements. For this reason, we try to address any gaps in middle school so that when they start high school, they can manage the pace and standards. Otherwise, we would recommend a non-college preparatory diploma, which meets state requirements and allows students to enter the community college system or pursue trade school.

In any of our grade levels, nothing prevents a student from following an accelerated path. Because all incoming students are placed in courses suitable to their assessed levels, they are never just plodding through material they already learned. And if they complete their courses early, they are just assigned the next set of courses—there is no need to wait for the next term. Again, this capability is only available to a school if their record-keeping systems can keep up with this kind of academic flexibility.

Bill Dembski:

What is the role of tests and exams at Studia Nova? It’s helpful when students know what they know and when teachers know what their students know. How do you track that knowledge?

Victoria Garmy:

We really do not focus on high-stakes testing except for the college prep high school courses, where this is a requirement. Tests are an invitation to take short cuts, and that is really hard to stop. Also, the current population of students has a real problem with test anxiety, and right now, exams and finals are not the best tool to rely on to determine if a student is learning.

Most of our testing is focused on skills assessment so that we can close the feedback loop and ensure that students are progressing. This also tells us if our courses were useful for increasing grade level achievement. Our testing program is more about testing whether our educational program is meeting its objectives.

We do need to do more work on measuring specific knowledge milestones. Right now our assessment program is mainly skills-based. We will be implementing key assignment tracking in all our courses over the next year to ensure that the learning of a given body of knowledge is properly assessed.

Bill Dembski:

Tell us some of the success stories of students that have come to you. Do you have students represented in each of the grades from K to 12? What have your students and their parents told you that they like best about your program? Where have they pointed to room for improvement? Have any of your students graduated the 12th grade and gone on to college? How have they fared in college?

Victoria Garmy:

Each success story had been folded into our curriculum and system. In our first year of operation, a young man came to us in the tenth grade, having dropped in and out of school plenty of times, and having a rough family life. His reading levels were maybe just at the fourth grade. Our entire literature program is now based on what we had to do to get this young man to read at the high school level.

We assigned him books like The Call of the Wild, but with audio, and made him read along with the audio. Because he was on-site, we could tell when he quit following along, and we could make him, but with good humor, start the chapter over whenever his eyes wandered. Then we asked him to write a summary of what he understood from the chapter at the end of every single chapter. At first his writing was almost impossible to read. We did not criticize. Eventually the writing improved, and within a year he was testing at high school level.

Our literature program presents students plenty of classical literature with a read-aloud component: they read the text and listen at the same time. This one-two punch is very, very effective at increasing comprehension levels. By adding a writing exercise, students must pause and recall, then express what they were learning.

We tend to have two clusters of students: those that just want to get high school over with and those that are preparing to go on to college. We don’t have very many students in the middle between these clusters right now. This is mainly because we are new and we are attracting more of the outliers at this time. For us, it is a great design envelope. Our system must effectively address remedial students while also preparing students for advanced study. So far, we have graduated a handful of students who went on to four-year colleges—some to community college first, others directly. We can’t claim any university graduates just yet since we are too new.

The main constructive feedback we get is in regard to sports and social opportunities. We are starting out as a small school, and each classroom is intended to stay small. We don’t do sports, and a student’s circle of friends will necessarily be limited. The environment we create is in fact perfect for learning and teaching positive social skills. But it lacks the amenities and nostalgia we often associate with going to school.

However, most of the time, our parents are just relieved. The arguments over homework stop. It is also a big relief for parents when they see the grade level gaps for their children closing rather than getting worse.

Bill Dembski:

What opportunities do your students, as they approach their sophomore, junior, and senior years in high school, have to take AP (Advanced Placement) classes? How about dual enrollment classes with a local community college? Do you have any provision for students achieving an International Baccalaureate? Are you able to handle specialized learning, such as teaching languages outside the usual Spanish, French, and German? How about Latin, Greek, and Hebrew? How do you prepare your students to get into competitive colleges or universities?

Victoria Garmy:

We have learned that the most effective way for students to improve their college selection chances is to take concurrent community college courses. This is fairly easy for our school to accommodate from a record keeping and paperwork perspective. Community college courses give the GPA boost needed, and also give the actual credit. AP courses give the GPA boost, but taking the class does not guarantee the college credit.

We have weighed the pros and cons of AP and dual enrollment, and dual enrollment wins hands down. We do not have plans for AP classes at this point in time. It seems like bad deal for students to take a more challenging class but not be guaranteed the college credit even if they do pull a five on the AP exam. We are interested in International Baccalaureate and will evaluate it more closely in the future.

Modern tools are revolutionizing the online teaching of languages—multi-media capabilities are very effective. Right now we are deploying an upgrade to our high school Spanish courses. Next we are looking to develop Latin courses. With the tools to build classes at our fingertips, we can take any textbook and virtualize it with many auto-graded assignments, and always a handful of teacher-graded assignments.

We find the internet replete with excellent open-source texts, and even better, old school texts that are in the public domain because the copyright has expired. Some of the best math text books we found were written by no-nonsense community college professors who published them free to the world.

Bill Dembski:

To accommodate twenty students at your facility during a three hour period, how many helpers do you need? Does your model need a well-educated teacher? Is it possible to outsource the teaching to online resources so that all you really need is a motivated supervisor?

Victoria Garmy:

One person can easily manage 20 students. And if a location wants to involve a parent volunteer, then the ratio is 1:10, which is exceptional. As we discussed, I am in this partnership with my mother, who looks after the students directly. Students are mainly busy and occupied, so there really isn’t any problem with one adult overseeing them. Most days my mother has very little to do and ends up engaging the students in conversation to keep herself entertained!

We specifically developed our educational model to prioritize passion over qualifications. Most of the work is mentoring and coaching, keeping students focused, and putting a dampener on chit chat. It’s not hard at all, and it’s pretty fun. The courses are complete with videos and interactive learning, so students do not require in-person lectures or real-time Zoom calls to deliver high quality education.

But we do know that not every passionate educator is going to feel comfortable factoring those quadratics or solving problems out of their depth. In such cases, when both the students and the teacher get stuck, we can stream online help to students. But we strive to use such resources sparingly to keep down our costs.

Bill Dembski:

Contrast what you are doing with homeschooling on the one hand, and on the other hand with alternatives to ordinary public schools, such as charter, magnet, and parochial schools. Do you have a memorable (brand) name for your educational model?

Victoria Garmy:

We are in-between homeschooling and standard private schooling. We fall under what is best called micro-schooling. But we make micro-schooling easier by handling all the red tape and providing a complete and accredited curriculum.

What is really different about Studia Nova is that we are structured to help people run micro-schools as their own small business. For example, an experienced homeschool teacher who wants to continue teaching as a service to the community can easily sign up and start teaching on our platform. Since we are hyper-focused on driving down costs, our micro-schools partners will be hard pressed to find a better value.

Now, there are many online curriculum companies. The main problem with most of these companies has to do with their primary customers, the public school system. These companies develop curriculum to adhere to calcified standards. They focus on the organizational requirements important to buyers rather than the end-user and end-use, namely, the student and the student experience.

Buyers love flashy, cartoony web pages. Yet flashy web pages are abhorrent to learning. Further, the curriculum is what it is—it’s set in stone. Curriculum companies typically do not have the flexibility to adapt and change based on student feedback. These systems can’t learn to be better systems. Some are good. Others are not so good.

Bill Dembski:

An objection that might be leveled against your approach is that it gives only a bare bones education. What about athletic opportunities? What about drama clubs? What about debate societies? Do you have any provision for enriching the learning experience of your students along these lines?

Victoria Garmy:

The objection is fair. I believe that dedicated organizations can be great at what they focus on, but if they focus on everything, they will be great at nothing. In our community, there are many club sports. There is a small business offering a drama club. And many other individuals in the community offer music lessons.

These people do a great job—better than we ever could. So I believe we should let the people best suited to the job do the job. With that said, we have had very interesting conversations with a local private music school that is considering adding on a micro-school to round out its offerings. The creative possibilities here are endless.

Bill Dembski:

How can people replicate your model? What are the key online resources that your students use? You are in California, a state known for red tape. How did you get your program to fly there? Given that you were able to get it to fly there, is your program replicable in all 50 states?

Victoria Garmy:

California indeed always adds an extra layer of paperwork that most states do not require. But in the end it is all just paperwork. There are many ways people can replicate our results, which is exactly what we want. Right now, if an individual lives in California, they can sign up on novaschools.org to start their own classroom. We provide business plan guidance, training, and lessons to be learned.

If an organization wants to start its own brand of schools, and run multiple classrooms with its own unique flair, such as a specific religious viewpoint, we can take it on as an organizational client and set it up with a custom website.

If we find someone ambitious who wants to start their own virtual school exactly as we have, but they want total control over their program and curriculum, we will provide our technology platform services. These include out-of-the box courses that may be tailored to their school needs. We also provide most of the documentation required to seek their own independent accreditation. This is the same successful documentation we used to obtain our accreditation.

Our longer term goal is to move the program we are offering into other states. In order to do so, we first need to research the educational requirements in each state. Only then can we ensure that our program will satisfy all state requirements.

Bill Dembski:

We’ve covered a lot of ground. Is there anything that you think we’ve missed and about which you would like to comment? How do you hope what you are doing will impact K-12 education? Where do you hope StudiaNova.org will be in five years? In ten years?

Victoria Garmy:

In the next year, we would like to see independent classroom operators opening their own little micro-schools, giving parents more choice then ever before. Then we would like to start packaging everything we learned from courses to technology to documentation to paperwork in order to get others to start opening schools. Eventually we want to bring this model to every state.

There have been so many groups trying to reform education for decade after decade. But mostly things just keep getting worse. I keep waiting for people to realize that screaming at the school board is not going to improve math scores and that we have to do this ourselves.

Many people care deeply about education. My own sister wrote an entire reading curriculum as a young mom just trying to teach her own daughter to read. Passionate and innovative people are out there. The problem is that there are no systems in place to deliver passion and innovation to school kids.

Studia Nova wants to create such a delivery system. This part has been totally missing. That delivery system is an ad-mixture of process, technology, regulatory compliance, documentation, and people. It is not one piece. It is all the pieces completely and efficiently reassembled.

If you care about children, we implore you to start re-engineering education with us. Be brave and open your own school. When we started, my mother and I did not bother to raise money. We just paid the bills until we got the enrollment to cover the basics. I work full time in the tech sector, and so I couldn’t supervise the kids day-in and day-out. But my mother could—she was retired and loved working with the kids. This partnership allowed me to focus on the technology platform, constantly configuring and deploying technology to reduce the administration overhead.

The point is, there are many ways people can team up to serve our children. Even if you are not interested in our services or technology package, reach out to me for a consulting appointment. I’ll lay out what we did and then you can go for it. We are especially interested in talking to people outside California. We can do it. You can do it.

Reference Information:

www.studianova.org — To learn more about our school, our mission, and our curricula.

www.novaschools.org — Visit if you are interested in starting your own micro-school, a “Nova School,” in California.

www.soundblends.com — To learn more about Studia Nova's selected early reader curriculum, visit Sound Blends.

I want to thank Bill for taking the time to learn about Studia Nova, we have partnered with a nation-wide church organization to put a classroom in quite a few of their major locations, we are thrilled that the model is creating time and space for faith formation and community involvement, all while producing great academic results. We would love to see more churches get involved and take education in their own hands!

In my previous comment, I mentioned the Harkness table approach to education first developed at Phillips Exeter Academy (PEA) in the 1930s. Here is a link to it

https://www.classpoint.io/blog/what-is-the-harkness-method

From what I understand the strength of this method is preparation. Since the class size is about a dozen students, each is expected to contribute so they must do the preparatory reading or problem solving in math. Each must contribute as soon all learn who is not preparing. One of my friends who is a graduate of PEA said you learn to fake it a lot. But it consistently produces a high level of learning.

I doubt it would be good for Nova grade school work but Nova might want to look into if for high school level students.