Ben Carson's Lost Interview on Education

An important interview on education retrieved from the "lost and found"

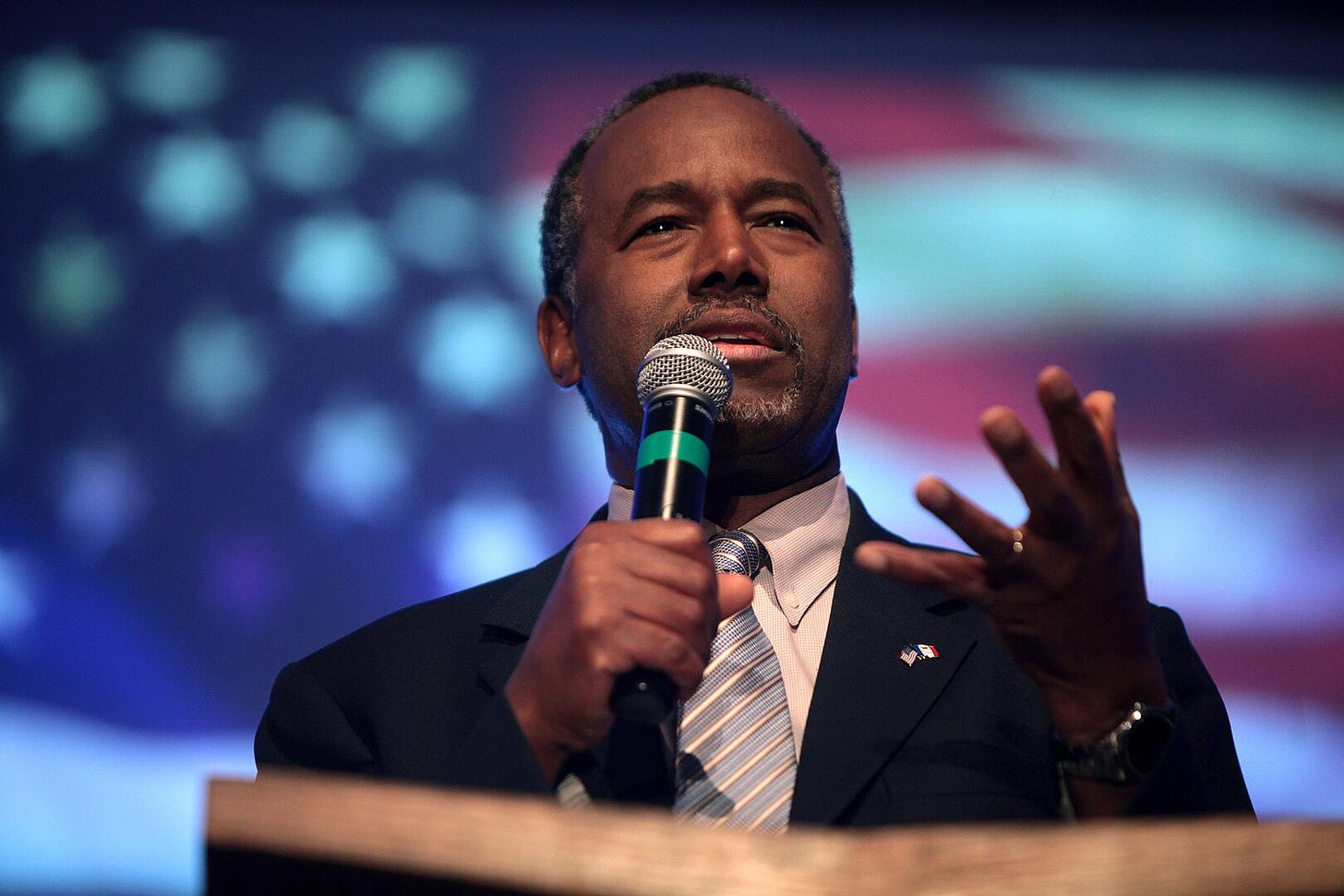

This interview with Ben Carson took place at an annual awards banquet of the Carson Scholars Fund (May 24, 2015 in Pittsburgh). Because I had supported the Carson Scholars Fund financially, I was able to arrange for my good friend and close colleague James Barham to interview Carson. The interview was posted for a time on an educational website with which I was associated. Subsequently, the site removed the interview, though not for political reasons (even though shortly after the interview, Carson ran for US president, eventually becoming Secretary of HUD in the Trump administration).

The reason for the interview’s removal was Google. Google penalizes websites that don’t stay in narrow lanes. It’s been said the riches are in the niches. Google increasingly enforces that maxim as an ironclad rule. As a consequence, websites, to be successful with the search engines, must strive for homogeneity and predictability. This interview didn’t fit the bill. As it is, Google’s AI stinks, and so websites, to play the SEO game, bow to its inadequate reading of their sites, often removing or not even creating content that readers would otherwise find interesting. Hence goodbye to this interview.

Ben Carson, M.D., is a world-famous pediatric neurosurgeon and professor of medicine (now retired from Johns Hopkins Hospital and the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine), the author or co-author of multiple books, a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and, as just noted, the former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. Most importantly for this interview, he is the co-founder, with his wife Candy, of the Carson Scholars Fund, an initiative that reflects his educational philosophy.

In this interview, James Barham and Ben Carson have a poignant and insightful conversation about education that is as relevant today as it was when it took place almost ten years ago. For readability and timeliness, I’ve made some light copyedits.

1. Education & Success

James Barham:

Dr. Carson, thank you very much for agreeing to this interview. It is an honor for us to be able to share your thoughts on education with our readers.

Ben Carson:

I’m delighted. Thank you.

James Barham:

Despite growing up poor in Detroit, you became a gifted pediatric neurosurgeon and professor of medicine at a world-renowned institution, Johns Hopkins University. What were the key points in your education that led to this remarkable success?

Ben Carson:

Well, the big thing was, I was not a very good student. My mother, who only had a third-grade education, always had a feeling that education was important. She worked as a domestic, cleaning people’s houses. She noticed that those people who were very successful did a lot of reading. They didn’t sit around watching TV a lot. And, after praying for wisdom, she came up with this idea: that we needed to be readers, and we needed to watch much less television. Now, my brother and I weren’t all that enthusiastic about that idea, needless to say. But in those days you had to do what your parents told you! So, we had to read the books.

And, I’ve got to say, after a while, I actually began to enjoy it. We were very poor, but between the covers of those books I could go anywhere. I could do anything. I could be anybody. I began to know amazing things. I used be so enamored of the smart kids because they knew so much. But all of a sudden, I knew stuff that they didn’t know! And I said: “The reason for that is because you’re reading. It got to the point where my mother didn’t have to make me read — she was saying, “Benjamin, put the book down and eat your food!” I was always reading.

And it really changed the trajectory of my life. Even later on, when I got to high school, and a lot of times the teachers were not able to teach because they spent the whole hour disciplining people. By that time, I was firmly into getting a good education, so I would go back after school, talk to my teachers, and say, “What were you planning on teaching?” They would always look forward to seeing me and knowing that they could share their lesson plan with somebody. I got a lot of extra tutoring. So, even though I was in an inner-city high school that wasn’t known for academics, I was able to get the kind of preparation that allowed me to get through Yale University.

2. Is Homework Too Demanding?

James Barham:

You have noted that in the 1800s, even people with only a grade-school education were well educated by today’s standards. As watered down as the curriculum is by comparison with former times, some professional educators argue it is still too demanding, and thus “unfair” to minority and poor students. For example, one vice principal of our acquaintance thinks that homework should be abolished for the sake of inner-city, mostly African-American grade schoolers. What would you say to her?

Ben Carson:

I would say that probably is a very archaic attitude: to believe that African-American students cannot achieve at a high level. There was a school that I visited in Dallas. The principal, Roscoe Smith, had been assigned there. It was the worst school in the Dallas area in terms of standardized testing. Terrible area, a lot of crime, teen pregnancy, etc. He went in there and he started cleaning up the graffiti and telling the students, “This is your school.” He got them involved. They had a little bit of pride in what was going on. He taught them slogans, such as “Obey your parents.” Always he ended with “Obey your parents.”

That perked up the ears of the parents, many of whom were not high-school graduates. But he wanted them to come to the school because he had programs designed to help them to learn, so that they could then in turn get more interested in what their children were doing. But the most important thing he did is this: he went out to the Dallas community, and he found people who came out of that neighborhood who were successful. He said, “I want you to come to my school. Just give me an hour’s notice — I’ll have all the kids in the auditorium. Tell them what you did. Tell them how you did it.” And he had a lot of people coming in there. Long story short: within a space of three years, they went from the bottom in the state in standardized testing to third from the top.

So, can they learn? Of course they can learn!

James Barham:

Of course they can.

Ben Carson:

But you have to provide the correct environment.

James Barham:

You think that homework is a part of that environment?

Ben Carson:

Of course it is. You know, you need to set the bar a lot higher. The expectations need to be much, much higher. People will rise to expectations or they will lower themselves to expectations.

3. The Role of Discipline in Education

James Barham:

In the same inner-city school district, it was recently forbidden to discipline students for such “minor” infractions as talking loudly during class, walking around the room, swearing at the teacher, even throwing objects across the room. What are your views on the place of discipline in establishing a classroom atmosphere conducive to learning?

Ben Carson:

Well, obviously, discipline is necessary for children. Training is necessary for children. Just like if you want to train a vine, you have to apply physical manipulation to get it to go where you want it to go, but as it learns, then you don’t have to do that. And I think it’s one of the reasons that a lot of people are opting for alternatives to the public school system, because you have so many progressives with this mindset that somehow all you’ve got to do is let the kids express themselves, and everything will be great.

But that just doesn’t work. And so, that’s one of the reasons that I push the whole idea of school choice and vouchers— to give people an opportunity to get out of those situations where their child is not likely to learn. You’ve probably noticed (you see it on television all the time): a new charter school is opening in one of the inner cities, and you’ve got lines and lines of people trying to get their kid in there.

4. Reading, Books, and Learning

James Barham:

You frequently recount how your mother made you and your brother turn off the television and read two books a week. You then had to submit book reports to her, which she pretended to read and grade. In a similar way, you challenge young people today to turn off not only the TV, but also their computers, iPhones, and other electronic gadgets, and pick up a good book. What do you regard as the benefits of reading books? And how would you distinguish the sustained reading required by books from the fidgety reading characteristic of electronic technologies?

Ben Carson:

Well, you know, our society has changed quite a bit. Before I retired, I noticed a lot of parents were coming to me, saying, “Should we put our kids on this [drug], because they’ve been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder?” You know, that used to be a rare thing, and now it’s like every fourth kid. And I’d ask them a couple of questions: I said, “Can they watch a movie?” “Oh yeah, they can watch movies all day.” “OK. Can they play video games?” “All day and all night.” I said, “They don’t have ADD.” I said, “Here’s what I want you to do: wean them off that stuff and substitute time with you, reading a book and discussing it. And then let’s talk about it in three months.”

Almost to a person, they would come back and say “it’s a different kid.” Why? Because nowadays as soon as a kid can sit up, we prop them in front of the TV. And what do you see? Zip, zip, zip; zoom, zoom, zoom. As soon as they get a little older, and they have some dexterity, we give them the controls for the video games. Zip, zip, zip; zoom, zoom, zoom. Now they’re in school, there’s a teacher up front, not turning to something every few seconds. You think they’re going to pay attention?

Their brain is on “super zoom,” so they’re not going to pay attention. You’ve got to slow it back down, and get it to a point where it can now grasp and digest the material. And you’ll find that reading is actually much more entertaining than the electronic media because you have to use your imagination to create the scenery, and you can create it the way you want, and it’s really a lot more fun. You’ve just got to slow them down long enough to get them involved in doing that.

5. What Happened to Respect for Education?

James Barham:

In your book, One Nation, you write movingly of the respect that your mother and other members of the African-American community in Detroit while you were growing up had for education. We can confirm that this was a common attitude among poor white folks as well, at least up until the 1960s.

What happened? Why, generally speaking, is that respect for education no longer there among poor people, black or white? And what can we do to restore it?

Ben Carson:

One of the things that really began to happen in a big way in the ’60s, which hadn’t been going on before, is that we began to really idolize sports stars and entertainers — lifestyles of the rich and famous. And those things became much more important to us than the scientist and the doctor and the professor and people who utilize intellect in order to achieve things. And this is not to say that no one in sports or entertainment is intellectual, but that’s not the aspect of their lives that’s emphasized.

And consequently, you’ve got so many of these young boys running around — for instance, in the inner city — thinking that they’re going to be the next Michael Jordan, or the next Michael Jackson, or somebody. I mean, if you can do that, and people are paying you millions and millions of dollars, you’ll think to yourself, “Why do I need to bother with algebra, grammar, and all this stuff? I don’t need to do that. I can buy and sell any school that I want.”

But what they don’t realize is only seven in one million will make it as a starter in the NBA. One in ten thousand will have a successful career in entertainment. So, your odds are not very good. Less than one percent of people who go to college on an athletic scholarship end up playing professional sports — and if you do end up playing, your average career span is three and a half years. So, we need to reorient people in terms of what real success is all about.

6. What is the Carson Scholars Fund?

James Barham:

The Carson Scholars fund gives awards to exceptional students and sets up reading rooms across the country. Could you give us an overview of this organization, especially how you came to start it and your aspirations for it? What are some of the success stories of the Carson Scholars Fund?

Ben Carson:

I would go into schools, and I would all see all these trophies: All-State Basketball, All-State Wrestling, State Baseball Champions. But there was never any hoopla about the academic superstars. At the same time, I was aware of many international studies that showed us languishing near the bottom of the list in terms of achievement—particularly in STEM areas.

My wife and I became concerned, and we said, “We have to do something about this.” So, we started 19 years ago giving out Scholar awards to children starting in the fourth grade for superior academic performance and demonstration of humanitarian qualities. They had to show that they cared about other people because we didn’t want people who were just smart but also selfish. We’re trying to establish the leadership for this country going down the road.

Now, we have over 6,700 Scholar awards given out in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The program has won several national awards like the Ronald McDonald House of Charity Award (only one organization a year), the Simon Award (one organization per year). Both of these come with six-figure checks. But obviously we don’t do it for the rewards — we do it for what happens.

You know, the teachers tell us that in many cases the GPA of the whole class goes up over the next year because now it’s not just the quarterback, or the baseball player, that everybody wants to be like. It’s the Scholar who has brought to their school this big, fancy-looking trophy that sits right out there with all the sports trophies. And the kids get to wear a medal. They go to a special banquet like the one that we’re out here for today. We try to put them on the same kind of pedestal as we do the athletes.

As far as the reading rooms are concerned, we put them in all over the country, in lots of different kinds of places. But especially we target Title I schools, where a lot of the kids come from. Homes with no books. They go to a school with no library (or a poorly furnished library). They’re not going to develop a love for reading. The problem is, 70 to 80 percent of high school dropouts are functionally illiterate.

So, we’re trying to truncate that downstream, so that we don’t get into that problem. We change the trajectory of their lives. And in most of the schools where we have our reading rooms, the teachers will tell you that the kids absolutely love going to the reading rooms. They’re decorated in ways that no kid could possibly pass up. Frequently, it reflects the character of the part of the country that they’re in. So, in Denver, some of the reading rooms have teepees in them and little ponies that they can get on. It is really, really cool.

James Barham::

Wonderful.

Ben Carson:

And they get points for the number of books that they read and the amount of time they spend in there. They can trade them in for prizes (like S&H Green Stamps). In the beginning, they do it for the prizes. But it doesn’t take long before it begins to change their trajectory—their grades, their self-esteem, the trajectory of their lives.

James Barham:

Just like it did for you?

Ben Carson:

Absolutely.

7. Public School & Music

James Barham:

You met your wife, Candy, who is an accomplished violinist, through your mutual love for classical music. Could you tell us how you first developed your interest in classical music? Would you like to see music training reinstated as an essential part of the elementary school curriculum as it was 50 years ago?

Ben Carson:

I would love to see music reinstated as an essential part of schooling. The culture that it brings; the knowledge that it brings. Just learning how to read music requires metrics, and I think that helps you with mathematics. A lot of scientists and doctors have a musical background—it’s very interesting.

I got interested in classical music because I wanted to be a contestant on my favorite TV program, GE College Bowl. They asked questions on science, math, history, geography, and I was really good at that stuff. But they also asked about classical music and classical art, and you weren’t going to learn that at Southwestern High School in inner-city Detroit. So, I took it upon myself. I would travel to the Institute of Arts day after day, week after week, month after month, until I knew every picture in there—who painted it, when they died. I always listened to my portable radio: Bach, Telemann, Mozart. And the kids in Detroit thought I was nuts: “A black kid in Motown listening to Mozart?” But I was boning up; I was getting myself ready.

It turned out to be tremendous. It opened up so many doors for me. One of the key doors it opened was when I was applying to Johns Hopkins. They only took two people a year in their neurosurgery program out of the top 125 applicants. How was I going to be one of them? Well, the fellow who was in charge of the residency program was also in charge of cultural affairs at the hospital. So, we started talking in the interview about medicine, neurosurgery—somehow the conversation turned to classical music. We talked for over an hour about different composers and their styles, conductors, orchestras, orchestral halls. He was on Cloud Nine. There was no way he wasn’t taking me after that!

I always like to tell young people: “There’s no such thing as useless knowledge. You never know what doors it’s going to open up for you.”

8. Education Reform

James Barham:

You have emphasized the importance of the role of public education in creating an informed citizenry upon which the health of our nation depends. And yet many of our public schools are failing in this task. How should American education be reformed to create an informed citizenry?

Ben Carson:

One of the things that I think we’re going to have to do is to reward teaching, good teaching. Right now, if you’re an excellent teacher, what do you get? More work to do. Pretty soon, you just start submitting to the unions and all these people who are trying to protect you (or think they’re trying to protect you). And that doesn’t work. We need to start thinking about new paradigms.

For instance, through virtual classrooms we now have the ability to put the very best teachers in front of a million students at a time instead of 30 students at a time. There are computer programs that can look at the way a kid solves five algebra problems. Based on how they solve them (or tried to solve them), it knows what they don’t know. It goes back and tutors them on that, brings them up to speed, so they can solve them.

It’s the same thing a good teacher can do, obviously, but a teacher can only do it for one student at a time. A computer can do it for a whole classroom or a whole school simultaneously—and at the speed of the patient . . . of the student. (You see, I’m still in doctor mode here!) But utilizing technology in that way can really help close the gap pretty quickly.

9. Wisdom & Common Sense

James Barham:

For all your obvious respect for learning, you have stressed the difference between knowledge and wisdom, and have written in your book, One Nation, “I would choose common sense over knowledge in almost every circumstance.” Yet much of American higher education puts a premium on knowledge and ideology over wisdom and common sense. What, then, would you say to our young people to help them attain wisdom and common sense, especially against the cultural forces that oppose these virtues?

Ben Carson:

I would say, “You need both. You need both knowledge and wisdom.” But I know a lot of very knowledgeable people who are not very wise, because wisdom tells you how to apply that knowledge—how to acquire and how to apply it. I seek wisdom from the source of wisdom, which is God. It’s a matter of looking at people around you who are successful, looking at people around you who are not successful, and figuring out: What are the traits that tend to characterize the unsuccessful people? What are the traits that tend to characterize the successful people? If you can then learn from that—inculcate that into your pattern of life—you’re a wise person.

A foolish person has to make every single mistake themselves, and it takes them a lot longer to make progress than someone who can watch you, you, and you, and say, “That didn’t work out. I’m not doing that.” It makes a big difference.

10. Freedom of Thought in America’s Universities

James Barham:

It’s vital that higher education give unconditional support to freedom of thought and expression. Unfortunately, an increasing conformity has crept into higher education, in which ideologies rule the day and dissident voices are shouted down or driven out. You yourself were disinvited from delivering commencement addresses more than once because views you hold were unwelcome. What has happened to freedom on America’s college campuses? And how can it be restored?

Ben Carson:

What has happened to it, simply, is that there are a group of people, and their philosophy is, “My way or the highway. We are all-wise, and anybody who disagrees with us doesn’t deserve to be heard—needs to be shut down. If possible, hurt them.” That’s completely antithetical to what the founders of this country fought for!

What can be done about it? I would say we need the kind of leadership in this country at a national level that will speak out against that kind of thing—not just turn your head and look the other way. Maybe even go so far as to change the function of the Department of Education. Make one of their functions monitoring our institutions of higher education for extreme political bias. And if it exists, they’re not eligible for federal funding. I think you’d find it would go away pretty quickly under those circumstances.

11. Leaders, Virtue, and Common Sense

James Barham:

On page 164 of One Nation, you present a wonderful summation of your moral philosophy, which centers on what you call “true compassion.” You say that true compassion is a rare thing, consisting in the willingness to extend a helping hand to one’s neighbor while also standing on one’s own two feet as a self-reliant and productive citizen. But to instill true compassion in the next generation, we need to be able to teach the traditional virtues of courage, temperance, fairness, and wisdom. Our question is this: What will it take to win back the hearts and minds of the intellectual leaders of our society to traditional moral virtues and plain common sense?

Ben Carson:

When the people with common sense get in power, they have to take the right attitude. Not an attitude of vengeance — “You did it to us, we’re going to do it to you.” That’s the wrong attitude. The right attitude is to show everybody (including those individuals you just talked about) the benefits of doing things the right way, of having morals and values, of saying there is something that’s right and there is something that’s wrong—of recognizing the Judeo-Christian values upon which this country was established, and which allowed us to rise to the pinnacle of the world (and to a higher pinnacle than anyone had ever risen) much faster than anyone had ever gotten there. To throw these things out is stupid. But what we have to do is, while we embrace these things, let anybody else do whatever they want to do. And then it becomes very clear what the advantages are.

12. The Shackles of Ignorance

James Barham:

You mentioned that in the 1800s, back when slavery was a reality, most people were far more educated than they are today, and that even the exams for passing the sixth grade were fairly rigorous, so much so that a college graduate today might not be able to pass them. You added that education liberates a child. So, what today would ignorance enslave a person to? What does a lack of education metaphorically enslave a child to? In the absence of actual, literal slavery, what is the metaphorical slavery that a lack of education shackles one to?

Ben Carson:

Education is the great divide in our society. It doesn’t matter what your ethnic background, your economic background: you get a good education, you write your own ticket—end of story.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of people who lack information. They’re very ill-informed. They’re not well-educated. And that’s the reason our founders put so much emphasis (particularly Franklin and Jefferson) on education—because they recognized that a well-informed populace is essential to the freedoms that we enjoy in our form of government. Why? Because uninformed people can be easily manipulated. For instance, in today’s world, given an uneducated, uninformed, unsophisticated population, slick politicians and dishonest media will come and say: “The unemployment rate is down to 5.4 percent. Oh, how wonderful everything is!”

But, of course, informed people know that that’s just not true. They recognize that it’s the labor force participation rate—the percentage of people eligible to work who are working—that has gone down steadily since 2009, and is now as low as it’s ever been in 37 years. But you have to be informed to know that kind of thing. If you’re not informed, someone easily comes along and tells you falsehoods, and you just lap it right up like a dog.

13. Success & Mediocrity

James Barham:

Recently, George W. Bush gave a commencement speech. When he congratulated the summa cum laude and the cum laude students for their excellent work, he jokingly added: “And to the C students, I would say: ‘You, too, can be president.'” What would you say to this valuation of mediocrity, where people are aspiring to mediocrity, as though just luck and pluck and circumstance can bring you all the rewards you need, and you don’t have to actually have intellectual horsepower?

Ben Carson:

I would say there are probably some people who did not achieve at the highest level but who are very smart. And, you know, I’ve had many opportunities to sit down with President Bush, have dinner at the White House, and various things. He’s always saying: “You know, all my opponents think that I’m stupid, but here’s the funny thing: They’re out there, and I’m in the White House.” And he actually reads 90 minutes every night before he goes to sleep.

James Barham:

Does he?

Ben Carson:

And, if you probe, you’ll find he’s really quite knowledgeable.

14. Closing Thoughts

James Barham:

Thank you very much for taking the time to share your insights with our readers. If there is one closing thought you would like to leave with our readers, what would that be?

Ben Carson:

That would be that the person who has the most to do with what happens to you in life is you. You get to make the decisions. You get to decide how much energy to put into it. You don’t ever need to look for anybody else to blame.

Its quite easy, when parents ask what they should do over the summer, we only recommend they read books of their choice. Reading books means your homework is more in your control, not worksheets you really don't want to do, its a chance to direct your own knowledge-building!

It seems that the Nova approach and Ben Carson’s approach can be married.

Nova only requires 3 1/2 hours of school. Why not add a book a week from a reading list for all that other time they have. I bet it would increase to more than a book a week fairly quickly.